Women’s Sports + Fitness Magazine (Writing Sample)

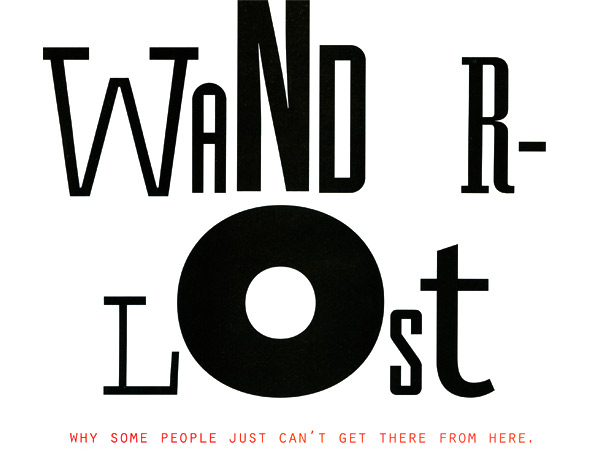

WanderLost: Why Some People Just Can’t Get There From Here

I knew my sense of direction was bad the day I got my driver’s license. I climbed into the seat of my parents’ car and prepared to drive to my best friend’s house. My parents had driven me there countless times, but today I’d be navigating the city streets alone. As I turned to ignition key, I was ecstatic. I was cool. I was grown-up. I was…lost. I realized I had no idea how to get there.

In that instant, I discovered the humiliating, frustrating truth: My sense of direction is nil. Zero. Zip. Zilch. I’m deaf to directions, blind to bearings, and stupid about signposts. The situation is so grim that I’ve coined a phrase to help me live with my spatial disorientation: It’s more important to know who you are than where you are. I say it loud and I say it proud, but I still have to wonder: Why can’t I figure out where I am, where I’m going, and, most importantly, how to get there? Last week, after turning the wrong way down a one-way street for the 16th time, I set out to answer the question: What’s my problem?

Reg Golledge, professor of geography at the University of California, Santa Barbara, says I’ve got a slew of them. For starters, he suggest that someone with what we commonly call “no sense of direction” probably has never been exposed to skills that help with orientation, such as map reading. “If you’ve never learned how to read a map or notice the angle of the sun,” he explains, “the question of understanding cardinal directions becomes much more difficult.” Aha. I can blame my parents for my shortcoming, because they never allowed me to navigate during my childhood on our afternoon drives in the country.

The first time I ever had a map shoved in my hand, I was a sophomore in college. My companion insisted I direct us around Cape Cod – okay, so he was busy driving. After the panic subsided, I took a deep breath, studies the twisting lines, stared at the curving road and…My god! They really did correspond.

That’s no surprise to someone like Robin Shannonhouse, executive director of the U.S. Orienteering Federation (USOF). Shannonhouse has been giving accurate directions all her life. “I’ve always had a good sense of direction,” she says. “When I was a little girl, my parents would take Sunday drives, and they’d invariably get lost. I thought they were tricking us; I didn’t understand why they couldn’t get home.” Oh the smug self-assurance of the topographically inclined.

Shannonhouse suggests that geographic orientation is a learned skill, not a genetic trait. “I think it’s self-taugh, based on what’s important to you. For me, I can’t enjoy myself in a new place without knowing my surroundings,” she says. “I’m not sure if this is a skill or a hang-up.”

As someone who rarely recognizes her surroundings, I’m not the one to ask. But Golledge interprets Shannonhouse’s way-finding abilities in several ways. People with a finely honed sense of direction, he says, rely on a combination of four strategies for finding their way in the world. People like me, he adds sympathetically, should listen and learn.

The first method is path following. Path followers preplan their trips, using sketch maps, verbal instructions, or road maps to find the best route to Grandma’s house. Rather than familiarizing themselves with their general environment, path followers are concerned with a specific segment of it – namely, the one that gets them where they want to go. (The directions said turn left. Oh, the other left…)

The second strategy relies on survey knowledge. It’s the mental equivalent of looking at a map, inspiring logical thoughts such as, “If I’m going to a café near the plaza, what’s the best way to get to the plaza?” Survey knowledge involves mentally reviewing the general area and locating an anchor point from which to begin a more specific search. (What’s wrong wit the café around the corner?)

Route learners are even more sophisticated navigators. They don’t just memorize directions or head for a general area, they notice landmarks—and remember them. They understand they layout of an area and can pinpoint themselves in relation to it. If a route learner passes a red barn on her right, for example, she’ll know that barn must be on her left when she returns. (Barn? What barn?)

At the top of navigational evolution chart is path integration. Path integrators have a knack for getting back to where they started. These way finders constantly update their position with respect to their home base and can return directly home. Path integrators instinctively find shortcuts that really are shortcuts; they view the world as an easily negotiable, two-dimensional map. (Uh, maybe I should just follow you there.)

Lucky them. When I ask Golledge how he’d categorize a woman who gets lost on her way home from somewhere she’s just driven to, he chuckles. “I’d say she better start paying attention,” he suggests.

Truth is, I really do try. (Well, sometimes.) But I’m simply more interested in the conversation in the car, the song on the radio, the thoughts in my head, than in watching for red barns and duck ponds. I suspect it’s related to my first response to mathematical word problems: The teacher wanted to know at what point John and Sue would meet if their trains were coming from X distances at Y speeds. But I was curious about something else: If John and Sue actually did meet, would they get along?

Some people might say that’s a typically female response to concrete data. But “typical,” it seems, is irrelevant when it comes to navigational skills. Remember the old joke about a man and a woman driving around lost because he refuses to get out and ask for directions? Well, it’s got a new punch line. According to Golledge, women may be more likely to ask directions—they often score higher than men on verbal communications tests—but that doesn’t mean they get lost more easily than men. In fact, says Golledge, “in [my] 25 years of study, no one’s found that men consistently outperform women.” Men’s reluctance and women’s willingness to admit they’re lost is based on psychological, not navigational, differences Translation: Machismo keeps him driving in circles.

But roughly equivalent test scores don’t mean men and women think – or act – the same way when it comes to navigation. Male orienteers are often dubbed “run and relocators,” says Shannonhouse. “The guys will look at the trail on the map and run until they reach a stream. Then they’ll look at the map, locate the stream and think, ‘Okay, here’s where I am.’ They’ll keep running until they find the next point of reference.

“Women, on the other hand, tend to over-read the map. They’ll find the stream, the cliff, the fork on the map and the stop at each landmark to see exactly where it’s located. I have to remind them not to stop at every checkpoint.”

For her part, Shannonhouse scoffs at the idea that women ask for directions more readily than men. “Female orienteers are very reluctant to ask for help. We think, ‘Why should I stop when I know I’m a great navigator?’”

Question is, how can I become one? Paying attention, following verbal directions, studying maps – no matter what the strategy, explains Golledge, those methods will ehlp create a clearer picture of my general environment. “If you’re not storing information,” he says, “you’ll have big holes in the mental map of your world.”

Golledge has one more suggestion to keep me from plummeting into the black hole of my spatial disorientation: Play more sports. “The more women are involved in sports, the better their spatial abilities tend to become. The skills used to play tennis, soccer or basketball are the same skills used for finding the way home: a sense of distance, direction, layout, placement. Remembering shops in a city is the same as noting players on a field. Although the move from a familiar to a complex space can be daunting, the process is essentially the same.”

So there it is, the answer to my prayers. Tennis, anyone?